Incentivizing Place

Overcoming an oversupply of cookie-cutter buildings and the potential impacts of AI on place.

Walking around Denver’s Golden Triangle neighborhood, it becomes painfully obvious just how overbuilt the neighborhood has become. Hundreds of new units have hit the market in recent months, many of which are in buildings that appear to be made from the same cookie-cutter. Big, boxy exteriors finished with materials that make the most expensive units in the neighborhood seem out of place. The buildings themselves also seem over-amenitized. There’s a luxury building with a Nordic cold plunge and sauna. Another one has a coffee-cocktail bar and a rooftop gourmet catering kitchen. Then there’s the pet parlours.

To Rhys Duggin, president and CEO of Revesco Properties, many of the new apartment buildings in the Golden Triangle seem like they were built for someone who doesn’t yet live in Denver.

“Denver has done a really good job of building large, 300 or 400-unit buildings for one demographic, which I affectionately call the bro demographic,” Duggin told me. “You’re a 24-year-old bro, and you roll into town and you need a place to stay. You think you need the pool and the golf swing bay and the wine cellar and the billiard room and the library and all these things you don’t use.”

Multifamily housing has become more homogenous since the COVID-19 pandemic. Whether driven by the needs of capital, outdated zoning laws, demographic changes, or the surge in demand for affordable housing, there seem to be dozens of developers in every city building the same big box buildings made out of the same materials.

This homogeneity evokes the urgency that America’s shortage of affordable homes has created for many households. Data from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies found half of renters—or roughly 42.5 million households in all—were cost burdened in 2022, meaning they pay more than the recommended 30% of their monthly income on rent and utilities.

It also represents how the pandemic changed our sense of place. Lockdown orders and social distancing requirements inspired people to begin thinking about how to make their buildings more adaptable. The rise of remote work allowed thousands of people to become digital nomads, thereby incentivizing temporary or mobile connections to places.

Designing homes for people influenced by these trends can seem like a tall task. But Duggin and his team at Revesco think they have devised an incentive to help their customers reconnect with the place they call home.

One solution they designed is their akin brand of apartments. Broadly speaking, the buildings are between 50 and 100 units and are “hyper-well located,” according to Duggin. The idea is that by putting all of the amenities a city has to offer at a renter’s front door, it incentivizes the person to connect with the neighborhood. That’s especially important in a neighborhood like Denver’s Golden Triangle, which connects to the city’s cultural and civic capitols.

Revesco has two akin properties in Denver, one in the Tennyson neighborhood and the other in the Golden Triangle. Another akin building is expected to be completed in the Bonnie Brae neighborhood next year.

“They go back to the reasons, in my mind, why cities exist in the first place,” Duggin explained. “The city is the amenity, not what’s happening inside your building. The reason we live in a city is to be out in the city and engage with it.”

The second solution Duggin and his team created is a little more “crazy,” he said. Revesco is running a sweepstakes where one akin resident will win $50,000 in cash and another will win a year of free rent. The sweepstakes runs from October 15 through mid-January 2026, with prizes being awarded at the end of the month.

Duggin admits that giving away cash is a controversial idea to some. However, he said that it makes a lot of sense right now, considering how the market has changed since the COVID-19 pandemic.

After the pandemic, there was a rush to build as many multifamily units as possible. Cities across the U.S., Denver included, adopted new zoning and permitting laws to fast-track the development of affordable housing. Now, many of those units are coming online, which has caused some submarkets like the Golden Triangle neighborhood to become oversupplied, Duggin said.

Giving away $50,000 is one way to stand out in a crowded market, but it’s also a way to help someone forge long-standing ties to Denver, Duggin said. That money could go a long way on a down payment for a median-priced home in Colorado, which is currently over $600,000.

“When you choose to live in a neighborhood, you don’t choose a building; you pick a neighborhood to be in that provides what you need,” Duggin said. “It allows you to be embedded in that neighborhood, in a very mature, livable way, and where residents look outward in the city versus inward.”

Potential impacts of AI on place

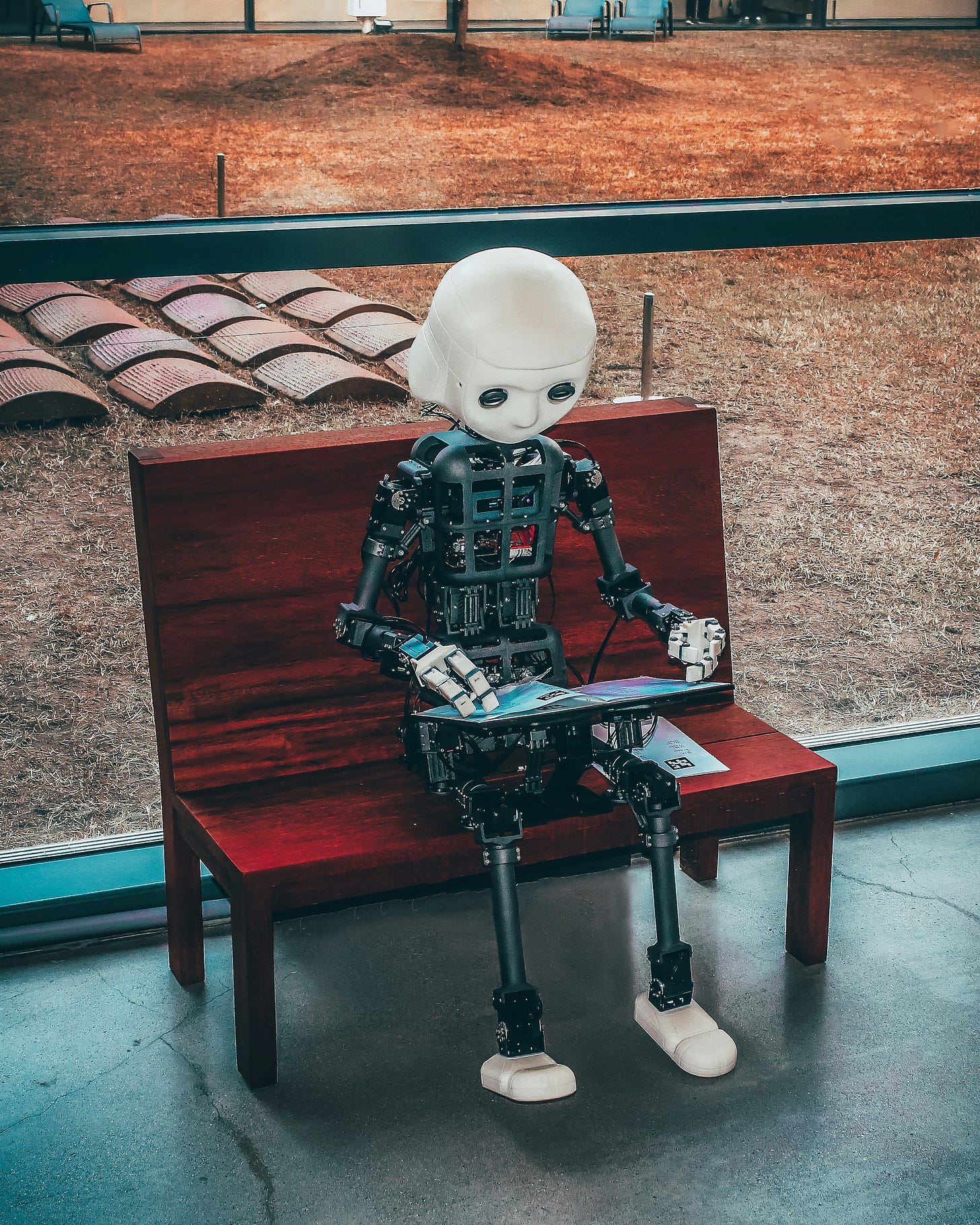

Everywhere you look, there seems to be an artificially intelligent something staring back. It could be a washing machine, a doorbell camera, or even a pair of reading glasses.

While the impact of AI on society is still being measured, there are some clear signs that it is already impacting the way humans interact with places.

There’s the positive side of AI, such as assistive robotic arms and AI-powered wheelchairs that help people gain greater accessibility to their surroundings. These inventions have become especially important for the elderly and people with disabilities.

Then there’s the bad side. Large language models that rely on incomplete or unrepresentative data have shown how AI systems can become biased and unfair. Some AI-powered facial recognition technology systems have been shown to have a significantly higher error rate for individuals with dark skin tones, thereby increasing their risk of being falsely detained or arrested. This also changes how people approach the public square, turning it from a place for all to a place for some.

There also appear to be burgeoning impacts on the expectations people have of places. AI promises to make the world more efficient, which could distort expectations of spontaneity and discovery within cities, according to Alex Baum, Regional Director for North America and Global VP of Strategy at Era-Co, a global consulting firm.

“I’ve seen the way that Yelp and Google Maps have changed the way people interact with cities, which is that it removes spontaneity, it removes discovery, and AI will only, I imagine, accelerate that,” Baum said.

Spontaneity and discovery are two of the most important aspects of any development, Baum added. On a neurological level, they release endorphins that can create lasting memories of a place. From a real estate perspective, they create buzz and excitement like a restaurant that has its main entrance in an alleyway instead of facing the street.

Baum adds that the impacts of AI on place remain unclear, but the potential impacts could be massive. Removing elements of spontaneity and discovery from places could radically change the way people interact with the places around them.

“If you have a device between you and the real world, the only thing that suffers is you and the real world,” he said.

Stories to watch

Most Americans use AI for housing market data (HousingWire)

Cryptocurrency enters the ultraluxury real estate market in Avalon and Stone Harbor (Philadelphia Inquirer)

The Hidden Cost of ‘Affordable Housing’ (The Atlantic)

Boston Is Piloting Window Heat Pumps in Affordable Housing (Next City)

Excellent analysis, thank you for highlighting this increasingly global trend of building these monolithic, overly-amenitized spaces that really make one wonder if developers are running a different algorithm than what cities truly need for their diverse populations.